Imagery from Venezuela Shows a Surgical Strike, Not Shock and Awe

Photo © Airbus DS 2026

In the early morning hours of January 3, 2026, more than 200 U.S. special operations forces (SOF) surged through Caracas to capture Venezuelan dictator Nicolas Maduro and his wife, Cilia Flores, in Operation Absolute Resolve. Extensive intelligence collection—overhead and on the ground—built a “pattern of life” on Maduro and provided the foundation for a successful mission: Maduro and his wife were captured, and no U.S. personnel were killed. It was an extraordinary military and intelligence achievement.

Using satellite imagery, combined with details that have emerged since the operation, CSIS was able to estimate the military activity and battle damage at four sites: the Fort Tiuna Military Complex, La Carlota Air Base, La Guaira Port, and El Higuerote Airport.

The picture that emerges from these images is that of a military operation in furtherance of a law enforcement mission—an operation laser-focused on the capture of Maduro with minimal collateral damage. This was not a “shock and awe” campaign intended to bring the entire Venezuelan security apparatus to heel with overwhelming force, although that too would be within U.S. capabilities given the force posture in the southern Caribbean. It was thus unlike the U.S. air attacks against Iraq in 1991 and 2003, where the objective was to shut the country down via a broad set of attacks on electrical, communications, and transportation infrastructure, thus forcing capitulation. No such targets were struck here.

In addition to these four sites, open-source reporting has confirmed that, at a minimum, additional strikes were carried out against communications infrastructure in El Volcán as well as air defenses in Catia La Mar and Fort Guaicaipuro. These more minor sites are not covered in this analysis.

U.S. forces focused on a limited number of sites, primarily the Fort Tiuna Military Complex where Maduro was known to have several bunkers. Air defense batteries and radars were also attacked to create a corridor for helicopters to enter Venezuelan territory and reach the target without interference. Many air defense sites remained untouched, however. U.S. military doctrine prescribes corridors: It was not necessary to take out the entire air defense system.

Venezuela’s regular military forces and their headquarters were also not struck. While an air defense unit was hit in the Port of La Guaira, for example, nearby Venezuelan navy ships were not. None of the buildings at La Carlota Air Base, reported to be part of the Venezuelan air force headquarters, were struck. This narrow target set may reflect a sincere desire to reduce casualties—both military and civilian. Even striking buildings at night, when many are virtually deserted, produces some casualties. It may also reflect a deliberate signal to the Venezuelan armed forces and the remainder of Maduro’s inner circle of the limited U.S. objectives. The Trump administration could have already decided to work through the existing Venezuelan structure and, therefore, did not want to destabilize or decapitate the military because it would be needed to keep order.

The inept force posture of the National Bolivarian Armed Forces of Venezuela (FANB) prior to January 3, 2026, facilitated the U.S. strikes. Air defenses were caught undisguised and out in the open, making them easy targets for U.S. attacks. It seems obvious in retrospect that these units should have been well camouflaged, possibly with decoys. However, units often fight as they train. If the training is undemanding—for example, taking place in the open, where it is easier to set up and conduct operations—units will do the same in wartime.

Venezuelan command and control, heavily degraded by electronic warfare and possibly cyber, failed to react until it was too late, allowing the force to enter Caracas. In the words of General Dan Caine, they “maintained totally the element of surprise.” Even in the face of imminent U.S. attack, the FANB failed to prepare adequately for the task at hand. It seems likely that, had the United States opted for a larger-scale campaign as its opening maneuver, the FANB would have suffered much greater losses than those reported. Years of neglect, combined with endemic corruption, low morale, and cronyism, have eroded the FANB’s operational capabilities significantly.

While U.S. strikes were limited, they still produced casualties. Current estimates report that approximately 75 people were killed, including 32 Cuban special forces who served as bodyguards for Maduro. Two civilian deaths have been identified, while residential buildings throughout Caracas were damaged. An investigation by Bellingcat found that one woman was killed when an AGM-88 anti-radiation missile detonated near an apartment block in Catia La Mar. Another civilian was reportedly killed when U.S. forces struck a communications array near El Volcán.

Fort Tiuna Military Complex

The sprawling military complex at Fort Tiuna constitutes the nerve center of the FANB. It is also reportedly where Maduro and his wife had taken up residence as the United States stepped up its military pressure against the regime. Accordingly, this site sustained the heaviest damage of the four locations reviewed by CSIS. However, the damage at Fort Tiuna is tightly focused, with no evidence of widespread strikes against barracks, training facilities, and administrative headquarters. This suggests a deliberate effort to isolate and neutralize those specific capabilities tied directly to rapid response and regime protection.

A January 3, 2026, Vantor image of Fort Tiuna shows the damage concentrated in several discrete areas within the complex. The most heavily damaged site is a motor vehicle maintenance and storage facility that is likely supporting a mechanized unit. The damage shows widespread destruction without clearly defined impact craters, suggesting it was struck by rocket or missile systems rather than bombs. Several heavy equipment transporters (HETs) are visible within the compound, further indicating that the facility supported a high-readiness mechanized unit capable of rapid movement. Open-source reporting suggests the unit may have been the FANB’s 312th “Ayala” Armored Cavalry Battalion. U.S. operational planners did not want this mobile force, with its considerable firepower, to mount a counterattack against SOF operators on the ground. Although special operators are superbly trained, they are light infantry without heavy weapons. They could easily be overrun by determined mechanized forces.

Satellite imagery also shows destruction of a nearby facility assessed to have housed emergency power generation equipment. Black smoke still visible a day after the strike indicates the ongoing combustion of fuel or oil. The location and configuration of the facility are consistent with probable backup power infrastructure supporting the nearby underground installations rather than routine barracks or administrative buildings.

Additionally, a large crater, measuring approximately 9.17 meters in diameter, was observed at a reported entrance to an underground facility (UGF) believed to be part of Maduro’s bunker complex. The extent of internal damage cannot be determined by satellite imagery alone. This may have been the facility where Maduro and his wife were captured. If so, then the damage may have been from SOF forces blowing open the sealed doors and getting inside.

In any case, there is no indication that these craters were caused by the kind of munitions that the United States used against Iranian nuclear facilities. Only B-2s carry these munitions, and B-2s were not listed among the aircraft involved in the operation. Further, the damage to the entrance could have been caused by any large surface-detonated munition. It did not require the penetration capability of special munitions for deep and hardened targets.

La Carlota Air Base

Two impact craters from munitions detonations can be seen slightly north of the runway at La Carlota Air Base. The relatively small footprint left by the strikes could indicate an effort to keep the risk of collateral damage to a minimum. La Carlota is surrounded by residential buildings and plays a dual-use civil-military role as both a private airport and home to the General Command of the Bolivarian Military Aviation.

Airbus imagery from January 4, 2026, shows impact points in open areas rather than against buildings or air base infrastructure. None of the runways, hangars, or buildings appear to have been struck, although there is some debris evident in the January 4 imagery. Satellite imagery confirms open-source claims that an uncamouflaged BUK-M2E surface-to-air missile system was destroyed at this location.

Three aircraft and a truck have been parked on the runway since at least January 4, for runway denial to prevent landing by larger aircraft. However, these cannot prevent helicopters from landing. The obstacles are a reasonable precaution against U.S. follow-on forces being flown in by medium cargo aircraft, such as the C-130, carrying supplies and heavier equipment. This move may have been suggested by the Cubans, as they had done when advising the rebel Grenadian government in 1983.

La Guaira Port

Located roughly 12 kilometers north of Caracas, La Guaira port was struck because of the presence of an air defense unit—not because it is a military facility. Satellite imagery taken two days after Operation Absolute Resolve took place shows damage localized to a single pier with two warehouses. The target point was between the two warehouses, where a Buk M-3 air defense missile system was reportedly located. Notably, the United States did not target the main loading and unloading docks at the port, nor the Venezuelan naval ships docked approximately 700 meters to the west.

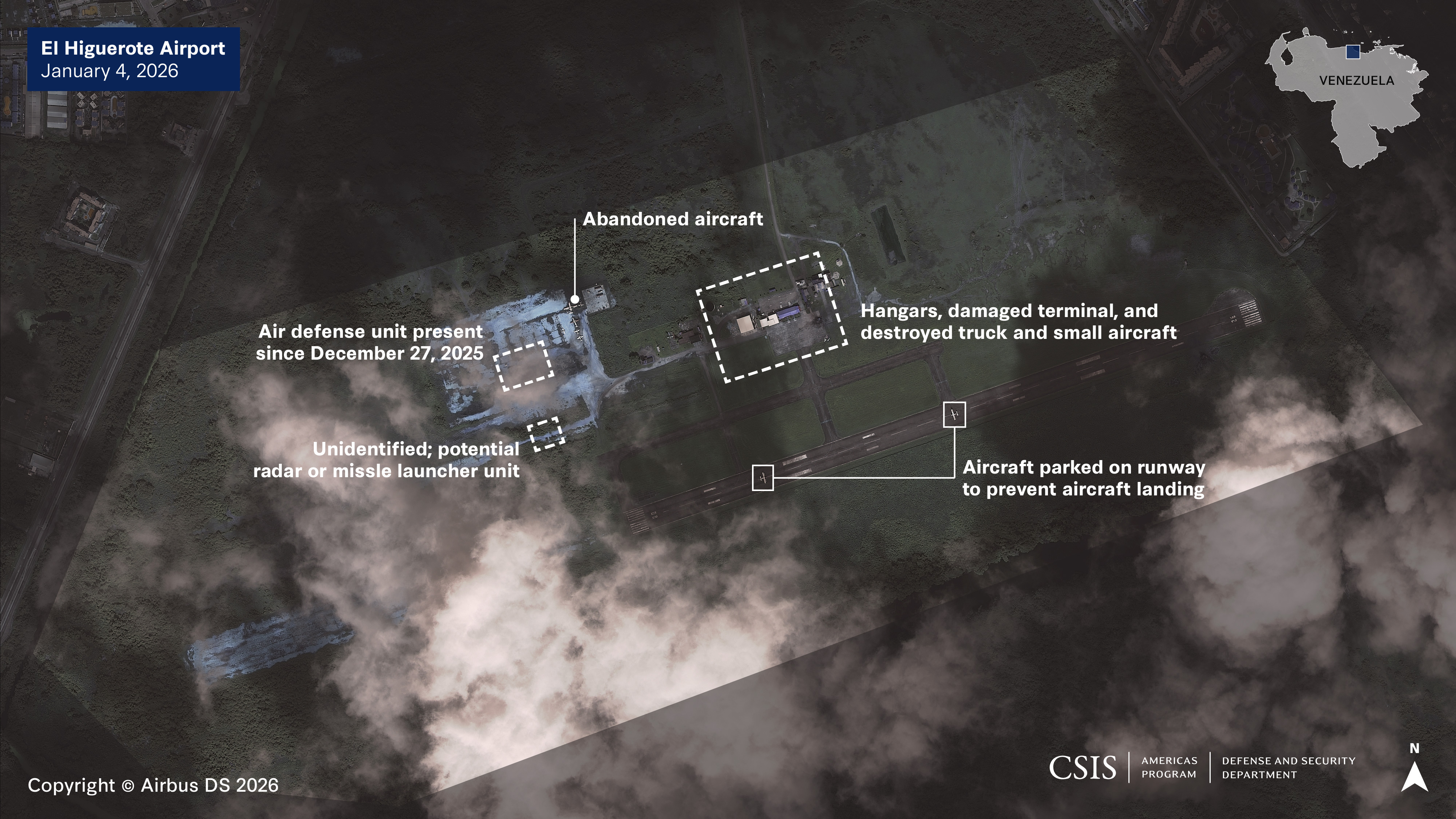

Higuerote Airport

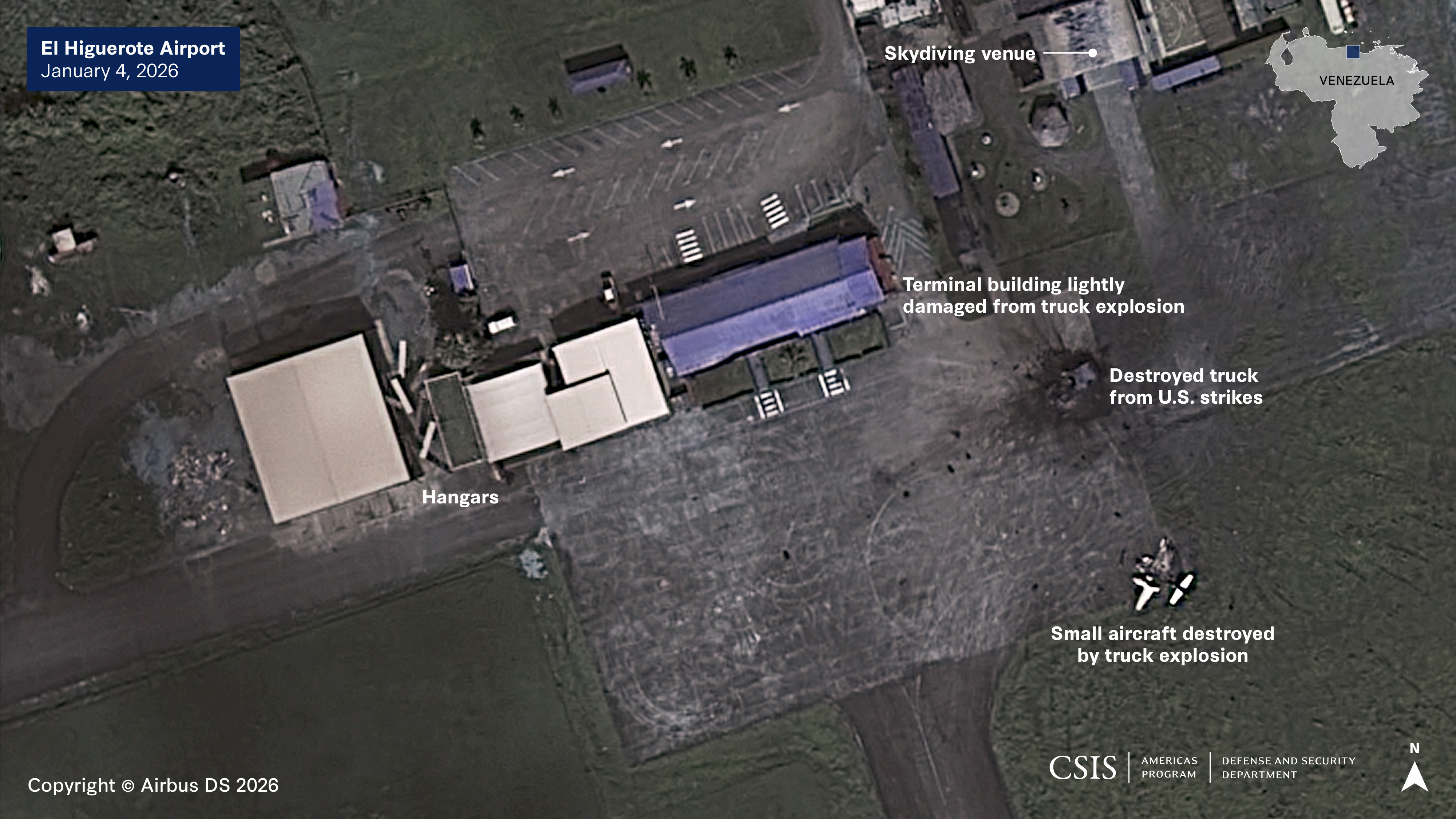

Higuerote Airport lies near the coast to the east of Caracas. As at La Carlota, aircraft were deliberately positioned on the runway to deny use by fixed-wing aircraft.

Additionally, post-operation imagery shows a destroyed truck near the terminal building, with a debris fan consistent with a precision strike. The resulting explosion likely caused secondary damage to a nearby small aircraft and light damage to the terminal. There is no indication of strikes elsewhere at the airfield, further supporting the assessment that the strike was narrowly focused rather than aimed at the overall operations of the airport.

Rather, the likely target of U.S. strikes at Higuerote Airport was an air defense unit, as seen in imagery taken in the days leading up to the operation. The only commercially available image after the strike, collected on January 4, does not conclusively confirm damage to the air defense unit due to cloud cover obscuring parts of the site. However, the presence of the unit prior to the strikes strongly suggests that the air defense unit was the intended target. The exposed posture of the unit suggests inadequate camouflage and defensive preparation by Venezuelan forces despite anticipation of potential U.S. action. There is some speculation that U.S. airborne assets entered or exited the country near Higuerote Airport, necessitating attack of the air defense unit there. Otherwise, there was no need to make an attack so far from the ground action. Indeed, the pattern of air attacks suggests that the U.S. helicopters entered from the east, concealed themselves behind the mountains, and exited straight north. Heliborne forces do not like to overfly the same territory twice lest adversary forces, having been alerted on the first pass, put up an effective defense on the second.

The Easy Part is Over

Operation Absolute Resolve required Herculean efforts on the part of all branches of the U.S. armed forces and intelligence community, who invested months in planning, rehearsing, and revising every detail of the mission. It is a testament to the skill and professionalism of the servicemembers involved that such a complex operation was executed with no loss of life among the U.S. force.

However, the successful exfiltration of Maduro and his wife was not an end in itself but the means to an end—getting Venezuela to cut its ties to malign external actors like Cuba, Russia, China, and Iran, increase its oil production through arrangements with oil companies, reduce illegal immigration to the United States, eliminate drug exports, and improve treatment of its population. To do this, the United States must skillfully manage its relationship with interim President Delcy Rodriguez, as well as triangulate between other poles of power like Defense Minister Padrino Lopez and Interior Minister Diosdado Cabello. It could well be the case that subsequent strikes (or even capture operations) will be deemed necessary to coerce these actors into pursuing U.S. goals. During his Mar-a-Lago press briefing on Maduro’s capture, President Trump noted that a second wave of strikes was ready, and subsequently warned that “if [Delcy Rodriguez] doesn’t do what’s right, she is going to pay a very big price, probably bigger than Maduro.” In the wake of Operation Absolute Resolve, the Venezuelan regime cannot afford to take such statements as empty threats. However, the U.S. Senate’s recent vote to advance a war powers resolution on Venezuela—likely to be voted down by the U.S. House—does indicate nascent and potentially growing opposition to further military action from within Congress.

Meanwhile, Secretary of State Marco Rubio has outlined the contours of U.S. objectives in Venezuela as first to stabilize the country, then to assist with its economic recovery, and finally, to hold elections, which will likely lead to democratic leadership. These are ambitious goals that cannot be achieved purely down the barrel of a rifle. In particular, the United States will need to provide the guarantees of legal and regulatory stability required to reopen Venezuela’s economy while ensuring that new revenues do not merely entrench the old caste of autocrats at the continued expense of the Venezuelan people.

The coming days and weeks will be especially critical for the United States. Its credibility and influence vis-à-vis the Venezuelan government are at its zenith. It should leverage this influence to ensure Delcy Rodriguez makes tangible and hard-to-reverse commitments toward winding back years of kleptocratic and criminalized rule.

Ryan C. Berg is director of the Americas Program and head of the Future of Venezuela Initiative at the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) in Washington, D.C. Mark Cancian (Colonel, U.S. Marine Corps Reserve, ret.) is a senior adviser with the Defense and Security Department at CSIS. Joseph S. Bermudez Jr. is a senior fellow for imagery analysis with the iDeas Lab and Korea Chair at CSIS. Jennifer Jun is an associate fellow and project manager for imagery analysis with the iDeas Lab and Korea Chair at CSIS. Henry Ziemer is an associate fellow for the Americas Program at CSIS. Chris H. Park is a research associate with the Arleigh A. Burke Chair in Strategy at CSIS.