Minerals at War: Strategic Resources and the Foundations of the U.S. Defense Industrial Base

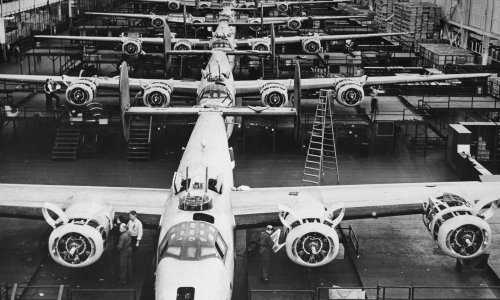

Photo: Keystone View Company/Archive Photos/Getty Images

Available Downloads

Introduction

Across major conflicts, the United States has repeatedly mobilized extraordinary state intervention—stockpiles, price controls, public financing, and foreign procurement—to overcome minerals supply shocks, only to dismantle these systems during periods of perceived stability. The historical record reveals recurring failures: overreliance on stockpiles absent industrial capacity, neglect of processing and refining, erosion of domestic expertise, and complacent assumptions about markets and allies. The post–Cold War drawdown marked the most severe rupture, hollowing out U.S. minerals capabilities and amplifying dependence on foreign, and eventually adversarial, supply chains. This paper traces the evolution of U.S. critical minerals policy in twentieth-century military industrialization, illustrating how a position of resource dominance gave way to economic and national security vulnerabilities. The central lesson is clear: Critical minerals security is a permanent national security challenge that requires continuous stewardship, integrated industrial policy, and durable engagement with allies, not episodic crisis response or faith in market self-correction.

World War I

In the early twentieth century, access to critical minerals was a defining determinant of military and industrial power. Europe’s leading powers—Britain, France, and Germany—secured the raw materials necessary for industrialization and rearmament not primarily through domestic production, but through colonial empires and overseas holdings. Although the British Isles possessed important domestic resources such as iron, tin, and coal, Britain’s true material strength flowed from its empire. India supplied manganese and tungsten; Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe) provided chrome; Canada delivered nickel; and Australia contributed lead and zinc. Germany faced similar constraints. With limited domestic mineral reserves, Berlin aggressively pursued stakes in foreign mines, from the United States to Australia, and even purchased the national debts of resource-rich countries to secure leverage over their mineral sectors.

This competition extended into emerging markets for rare earth elements (REEs). In the early 1900s, the German Thorium Syndicate and the Austrian Welsbach Company dominated global monazite extraction in Brazil and India, flooding markets with cerium, lanthanum, and thorium. Their control over these deposits effectively pushed the United States out of the REE industry; the United States would not resume domestic production until 1952.

Resource pressures intensified dramatically in the years leading up to World War I. Between 1909 and 1914, Britain and Germany entered an intense naval and military arms race, dramatically increasing demand for strategic minerals. A single battleship required 8,000–12,000 tons of steel and roughly 200 tons of copper wire. Producing that steel depended on alloying minerals such as nickel, chrome, and manganese, while zinc provided corrosion-resistant coatings. Ammunition was similarly mineral intensive, relying on nitrate-based explosives packed into brass casings made from copper and zinc. Even early wartime aircraft added to the competition for resources, as their lightweight frames required aluminum derived from bauxite.

World War I exposed the fragility of the United States’ own critical mineral supply chains. In 1914, the United States was among the world’s leading mineral producers, accounting for approximately 55 percent of global copper output, 40 percent of coal and iron, and 30 percent of lead and zinc. Yet domestic abundance masked deeper vulnerabilities: The United States lacked the international partnerships, strategic stockpiles, and coordinating mechanisms required for wartime mobilization.

As the war progressed, industries essential to munitions, aviation, and communications faced acute shortages, particularly of platinum. In the early 1900s, the Ural Mountains in Russia supplied roughly 95 percent of the world’s platinum. When the Bolshevik Revolution erupted in 1917, Russian exports contracted sharply, leaving the United States scrambling to secure alternative sources. This scarcity prompted President Woodrow Wilson to impose restrictions on nonessential uses of the mineral, such as jewelry. Colombia, then the world’s second-largest producer, initially appeared to offer relief, but negotiations faltered when U.S. officials learned Bogotá intended to establish a state monopoly to extract concessions on U.S. shipping tonnage. Before an agreement could be reached, the war ended, demand receded, and talks collapsed. A stable supply emerged only in 1923, when major new platinum deposits were discovered in South Africa, which quickly became the United States’ primary supplier.

These wartime improvisations exposed deeper structural weaknesses. Competition between the Army and Navy for materials drove up costs and fragmented supply chains, while the nation’s geological wealth failed to translate into the industrial capacity necessary to deploy those resources at scale.

Only in the final phase of the war did the federal government take sweeping, decisive action on critical minerals. The War Industries Board was established in July 1917 to coordinate U.S. industrial production by establishing priorities, setting prices, and standardizing goods to ensure the nation and its allies were adequately supplied for the war effort. In October 1918, the War Minerals Stimulation Law became the first large-scale U.S. attempt to intervene in mineral markets for national security. As a New York Times article on September 12, 1918, reported, the bill “authorize[d] the President to take over and operate undeveloped or insufficiently developed deposits of metals or minerals named in the bill, or mines, smelter, or plants which in his opinion are capable of producing minerals needed for the war.” The legislation created a $50 million fund to execute its objectives and empowered the president to establish one or more corporations to stimulate production and oversee distribution. It specified the minerals eligible for support—including manganese, phosphorus, potassium, radium, mercury, and 36 others—while explicitly excluding gold, silver, zinc, copper, and lead. All authorities granted under the act expired two years after peace was declared.

The United States emerged from World War I as one of the primary suppliers of metals to a devastated Europe, but peacetime demand quickly collapsed. Continued high U.S. production flooded global markets and drove plummeting prices. Producers engaged in fierce, uncoordinated competition, producing copper, zinc, and other base metals at far above sustainable levels. Temporary stabilization came through voluntary export associations, most notably the Copper Export Association, which brokered large import orders for credit from reconstructing European economies. When European demand receded in late 1923, however, these associations dissolved and U.S. mineral producers entered a prolonged depression, marked by oversupply and price collapse.

At the same time, policymakers were attempting to draw lessons from the country’s wartime minerals insecurity. In 1920, War Industries Board Chairman Bernard M. Baruch urged the federal government to craft a wartime procurement strategy for strategic and critical materials, and Congress did take initial steps to shore up the country’s mineral supply. The National Defense Act of 1920 directed the assistant secretary of war to ensure “adequate provision for the mobilization of matériel” and created three key planning bodies: (1) the Planning Branch in the Office of the Assistant Secretary of War, (2) the Army Industrial College, and (3) the Army and Navy Munitions Board. The Army and Navy Munitions Board, specifically, was tasked with studying resource shortfalls from WWI and minimizing interservice competition. Its 1921 assessment, known as the Harbord List, identified 28 minerals likely to be critical in a future war. Six additional lists were produced in the following 15 years, but in an era defined by fiscal restraint and isolationism, these analyses produced no substantive policy action. A coherent national materials strategy failed to emerge.

The National Defense Act of 1920 did, however, set off a frenzy of industrial mobilization planning, including a series of four critical Industrial Mobilization Plans (IMPs) released between 1930 and 1939. These plans envisioned four “superagencies” to oversee wartime coordination of industry, selective service, public relations, and labor. The IMPs were hotly debated. Critics argued that they failed to account for U.S. obligations to both domestic production and allied support, and that they did not adequately address how essential materials such as steel, copper, and aluminum would be allocated under wartime pressures. These disputes overshadowed the development of the plans themselves. As a result, on the eve of World War II, the United States once again faced the prospect of entering a major conflict without a coherent system for securing or distributing its critical mineral supplies.

The Great Depression further compounded this unpreparedness. Following the October 1929 stock market crash, global economic activity collapsed, driving down demand for nearly all minerals. Commodity prices plunged, and mining operations across the country contracted sharply. Gold was the lone exception. In 1933, President Franklin D. Roosevelt nationalized gold through the Emergency Banking Act after the Federal Reserve Bank of New York could no longer honor currency-to-gold conversions. The subsequent Gold Reserve Act of 1934 reset the price of gold and effectively resurrected the gold standard, restoring financial links between the United States and the global economy as domestic conditions began to stabilize.

By the late 1930s, despite two decades of warning signs, the United States again stood on the brink of global conflict without a coherent framework for securing or allocating critical mineral supplies. The experience of World War I had demonstrated a central lesson that policymakers struggled to institutionalize: Mineral security is not a function of geology alone, but of planning, coordination, and sustained state engagement with markets.

World War II

Just as the United States’ economy began to stabilize following the Great Depression, World War II erupted in Europe. Although the United States had not yet entered the conflict, policymakers increasingly viewed U.S. involvement as inevitable and moved to avoid the supply failures that had plagued World War I.

Central to this effort was the creation of the nation’s first formal strategic materials stockpile. The first official purchase of strategic and critical minerals for wartime was authorized by the Naval Appropriations Act of 1938. The following year, the United States adopted the Strategic and Critical Materials Stock Piling Act of 1939. This act authorized $100 million for the purchase and retainment of domestic and foreign stocks of strategic and critical materials. In February 1940, President Roosevelt requested an additional $15 million to expand these purchases. In his letter to Congress, Roosevelt noted both that commercial stocks of vital raw resources in the United States were low and that, “In the event of unlimited warfare on sea and in the air, possession of a reserve of these essential supplies might prove of vital importance.” Throughout the war, the president designated over 100 different minerals and metals as essential.

Stockpiling was only one component of a broader wartime strategy to secure supplies and deny access to adversaries. Domestically, the Roosevelt administration imposed strict export controls in July 1940, requiring licenses for shipments of critical minerals. Violators faced fines of up to $10,000 or imprisonment. After the attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941 and the United States’ formal entry into the war, the government closed the country’s gold mines and returned drafted miners to civilian status, redirecting skilled labor toward the extraction of strategically vital minerals. In February 1942, the government began paying premiums and establishing ceiling prices for copper, lead, and zinc to incentivize greater extraction at still competitive prices. Later that same year, the government went so far as to redesign the penny and nickel to use less copper and nickel. The U.S. Mint’s changes saved enough copper to manufacture 1.25 million artillery shells.

At the same time, the U.S. Bureau of Mines (USBM) dramatically expanded its role. Established in 1910 to improve mine safety and efficiency, the bureau had already contributed to wartime efforts during World War I, from cataloging technical expertise to developing gas masks. During World War II, the USBM became a central actor in mineral discovery, identifying new domestic deposits of copper, cobalt, and molybdenum. These efforts helped fuel a massive expansion of U.S. industrial capacity. By 1944, aluminum output had tripled, magnesium production had increased fiftyfold, and steel output was one-third higher than in 1940. By the end of the war, the United States was producing roughly 45 percent of all global combat munitions and arms.

Internationally, the United States pursued aggressive mineral diplomacy and preclusive purchasing to secure supplies. In Latin America, the USBM, working with the Department of State, investigated 440 mineral deposits, leading to new discoveries of tungsten, tantalite, and other materials in Mexico, Brazil, and Peru. In Africa, the United States subsidized the colonial government of the Belgian Congo to mechanize and accelerate copper and cobalt production. The U.S. government also pressed British colonial authorities to curtail gold mining in favor of strategic materials. In the Caribbean, the United States financed a state-of-the-art nickel mine in Cuba in 1943. At this time, the Reconstruction Finance Corporation and the newly formed War Production Board allocated federal financing to import these materials in large quantities. As a result of this purchasing, only 3 of the 15 materials stockpiled during WWII were sourced domestically.

Following the end of the war in the Pacific, President Harry Truman signed the Strategic and Critical Materials Stockpiling Act of 1946, amending the 1939 law and further strengthening federal authority to acquire minerals. Wartime mobilization had significantly depleted domestic reserves, making continued stockpiling necessary. Truman was publicly reluctant to sign the bill, which expanded the stockpile’s cost and reaffirmed the Buy American Act. Although the legislation allowed foreign sourcing when more economical, Truman feared it could be used to subsidize domestic mining inefficiently. In his signing statement, he cautioned against excessive resistance to foreign sourcing, emphasizing that “a large volume of soundly based international trade is essential” to U.S. prosperity and global stability. This tension—between domestic production ambitions and geological reality—became a defining feature of U.S. critical minerals policy. The war demonstrated that complete mineral self-sufficiency was geologically impossible; the United States had imported approximately $2 billion worth of minerals (roughly $31 billion in today’s dollars) from 53 countries. After 1945, strategy shifted toward maintaining limited domestic reserves of the most essential materials while relying on alliances and trade for the remainder.

Institutional reforms followed. The National Security Act of 1947 sought to strengthen wartime industrial planning. This act not only established the Air Force and the Department of Defense (DOD) but also created the National Security Resources Board and the Munitions Board. Supported by interagency advisory bodies, the Munitions Board developed a list of 54 strategic material groups by 1950. At that time, the National Defense Stockpile held materials valued at $1.6 billion, with an additional $500 million on order.

The end of World War II also marked the collapse of European colonial empires. Newly independent states across Africa and Asia increasingly leveraged their mineral resources for economic development, even as Cold War rivalries transformed mineral-rich regions into strategic battlegrounds. Minerals became tools of diplomacy and coercion, not merely commercial inputs. Thorium illustrates this shift. Prior to independence in 1947, India was a leading global supplier of thorium, a material critical to nuclear research and U.S. weapons development. After independence, India revisited this strategy and enacted the Atomic Energy Act of 1948, banning exports of radioactive materials. The cutoff constrained U.S. nuclear efforts at a critical moment.

In some cases, decolonization opened new avenues for mineral diplomacy. In 1951, amid severe food shortages, India sought U.S. assistance. Congress approved a two-million-ton grain shipment on the condition that a strategic materials clause be included. The resulting agreement exchanged 500 tons of thorium-rich monazite for a $190 million food loan—an early example of minerals-for-aid diplomacy that would become a hallmark of U.S. Cold War strategy.

Concerns over foreign dependence drove renewed domestic exploration. In 1949, prospectors searching for uranium in California’s Clark Mountain Range discovered significant bastnaesite deposits, rich in light REEs such as neodymium and cerium. By 1952, production began at the Mountain Pass mine and from 1965 to 1995, the mine would dominate global rare earth supply, anchoring U.S. leadership in early materials science.

The end of WWII and simultaneous beginning of the Cold War between the United States and the Soviet Union further underscored the risks of foreign dependence on minerals. After the 1948 Berlin Blockade, the Soviet Union cut off shipments of manganese and chromium—which had been supplying one-third and one-quarter of U.S. demand, respectively—in retaliation for Western export controls. These restrictions had both immediate and significant impacts. The United States responded by rapidly diversifying supply. Manganese imports shifted to the Gold Coast (now Ghana), India, and South Africa, supported by coordinated investments in railways, ports, and power infrastructure financed by U.S. and World Bank loans. Chromium supplies were similarly diversified through increased exports from Turkey and the Philippines, while a domestic recession eased demand pressures.

By the end of the 1940s, U.S. experience had clarified two enduring truths. First, complete mineral self-sufficiency was neither realistic nor necessary. Second, secure supply required a combination of limited domestic stockpiling, coordinated industrial policy, and sustained engagement with allies and producers abroad. This dual-track approach—balancing national reserves with alliance-based trade—became the foundation of U.S. critical minerals strategy for the remainder of the twentieth century and would shape U.S. critical minerals policy through the next major national security crisis.

The Korean War

The outbreak of the Korean War in June 1950 forced the United States into a renewed phase of emergency economic mobilization and dramatically reshaped federal critical minerals policy. Within months, Congress appropriated $2.9 billion for emergency stockpile purchases and enacted the Defense Production Act (DPA) of 1950, granting the president sweeping authority to mobilize U.S. industry for national defense. The DPA explicitly authorized federal support for the “exploration, development, and mining of strategic and critical minerals and metals.” Expansion targets were established for base metals such as chromium, copper, manganese, and sulfur, as well as for alloying metals—including nickel, tungsten, molybdenum, and cobalt—essential for producing the high-temperature, high-performance steels underpinning modern military systems.

Rather than relying solely on market forces, the federal government actively promoted domestic mineral production and processing. Under Title III of the DPA, policymakers deployed a broad tool kit that included loans, loan guarantees, purchase agreements, guaranteed prices and output levels, and accelerated tax amortization. Despite the long lead times typical of mineral development, these incentives produced rapid results. By 1953, the government had executed more than 425 exploration contracts, identifying new domestic sources of uranium, tungsten, beryllium, copper, and manganese. Federal support extended beyond extraction to processing capacity. One prominent example was a $94 million, government-financed copper-molybdenum complex in Arizona that integrated a mill, smelters, power plant, townsite, and rail connections. Additional initiatives included rehabilitating a copper mine in Michigan, constructing a facility in Minnesota to process low-grade manganese ore, and doubling domestic germanium production to meet surging electronics demand.

Supply expansion was paired with aggressive demand management. In January 1951, the National Production Authority prohibited the use of copper in more than 300 consumer products, restricting the metal to applications with no viable substitutes. Hoarding for resale above market prices was banned. A voluntary price freeze on copper, lead, and zinc followed, but quickly proved unenforceable. Within weeks, Charles E. Wilson, director of the newly created Office of Defense Mobilization, called for comprehensive wage and price controls. On February 1, 1951, the Economic Stabilization Agency issued its General Ceiling Price Regulations, fixing prices at their highest levels during a December 1950–January 1951 base period. Producers criticized the system as unworkable—particularly in international markets—and pricing confusion intensified. A temporary government-wide wage and price freeze was soon imposed to restore stability.

Throughout the Korean War, stockpile policy reflected the volatility of mineral markets. Although the president authorized the release of roughly $60 million worth of materials from the National Defense Stockpile, its actual value rose sharply—from $1.15 billion in 1949 to $4.02 billion in 1952. The government commitment to expanding the stockpile increased even more dramatically, from $3.77 billion to $7.49 billion, as policymakers sought to buffer the nation against future supply disruptions.

At the same time, the federal government accelerated mineral exploration. The DPA authorized financial assistance to private firms producing materials deemed critical to national security, prompting the creation of the Defense Minerals Administration within the Department of the Interior in 1950. In 1951, its exploration functions were transferred to the newly established Defense Minerals Exploration Administration (DMEA). By 1953, the DMEA had executed 517 exploration contracts covering 26 minerals across 32 states and territories, with government funding covering more than half of the $25 million in total exploration costs.

Recognizing that domestic resources alone might prove insufficient, the Truman administration also turned to longer-term strategic planning. In 1951, it established the President’s Materials Policy Commission (PMPC), known as the Paley Commission, to assess future material requirements. The commission warned that U.S. industry faced growing shortages of minerals critical to communications, transportation, agriculture, and defense. While it examined foreign reserves as a potential solution, it cautioned that heavy reliance on overseas supplies could generate both geopolitical vulnerability and accusations of economic imperialism. Instead, the PMPC advocated leveraging development assistance to secure access to strategic materials through partnership rather than coercion.

This logic aligned closely with the Point Four program, announced by President Truman in 1949 to promote technical assistance and capital investment in noncommunist developing countries in Latin America, Africa, and Asia. Under this framework, mineral diplomacy became a core element of U.S. engagement with the Global South. In 1952, the Defense Materials Procurement Agency—the PMPC’s successor—dispatched geologists to map strategic mineral deposits across developing countries. These surveys generated highly detailed intelligence on foreign mineral resources, down to precise coordinates and mineral ore grades, guiding U.S. investment and procurement decisions and enabling preemptive action to secure supplies. In Afghanistan, for example, newly identified beryl deposits—critical for nuclear weapons production—prompted the United States to commit to purchasing the country’s entire output within two years, thereby preventing Soviet Union access. Across multiple regions, Point Four missions helped identify mineral deposits, modernize transportation networks, and establish regulatory frameworks conducive to private investment. By the late 1950s, however, the Department of the Interior’s mineral-focused activities under Point Four diminished as political enthusiasm for the program waned during the Eisenhower administration.

After the Korean War ended in July 1953, U.S. mineral policy continued to adapt. During the mid-1950s, the federal government increasingly used barter arrangements to secure foreign supplies. The Agricultural Trade Development and Assistance Act of 1954 authorized the exchange of surplus U.S. agricultural commodities—often denominated in local currencies rather than dollars—for strategic minerals. Sections 202 and 203 of the act explicitly permitted barters for strategic minerals. In 1959, for example, the United States exchanged $6 million of wheat for Haitian bauxite. Similar deals secured Turkish chrome, Indian manganese, and Bolivian tin. Managed by the Commodity Credit Corporation, these transactions advanced both economic and geopolitical objectives, reinforcing U.S. influence in regions where the Soviet Union and China were pursuing parallel barter diplomacy. As a matter of policy, the United States excluded the Soviet Union, China, and Eastern bloc countries from these arrangements.

By the late 1950s, evolving military doctrine further reshaped minerals policy. Anticipating shorter, faster-moving conflicts, President Eisenhower reduced the rapid-mobilization planning horizon from five years to three in 1958. This shift reignited debate over stockpile composition. Many materials acquired through programs such as the Agricultural Trade Development and Assistance Act proved to be of substandard or non-stockpile-grade quality, raising questions about their usefulness and cost. Policymakers ultimately concluded that only materials meeting strict quality standards—and whose disposal would not destabilize domestic markets—should be retained. At the time, 63 of the 75 materials in the strategic stockpile were deemed surplus, marking the beginning of a long process of reassessing and refining stockpile policy.

The Korean War and early Cold War period clarified enduring lessons for U.S. critical minerals strategy. Mineral security required sustained state engagement, not episodic crisis response; domestic production had limits that could not be overcome by policy alone; and access to global supply chains depended as much on diplomacy and development partnerships as on stockpiles and controls. These insights would continue to shape U.S. critical minerals policy through subsequent conflicts and into the modern era.

The Cold War: 1960s

By the early 1960s, a degree of complacency had settled over U.S. materials policy. The hard lessons of World Wars I and II had receded, and raw materials were no longer viewed as an immediate constraint on national power. At the same time, the Soviet launch of Sputnik in 1957 ushered in an era of intense scientific and technological competition, compelling the United States to redirect substantial resources toward space exploration and related technologies. Against this backdrop, policymakers began to reassess a strategic stockpile that had ballooned rapidly during the Korean War and the early Cold War.

This reassessment gained momentum in 1962, when President John F. Kennedy publicly declared his astonishment that the National Defense Stockpile contained $7.7 billion in materials—approximately $3.4 billion more than estimated wartime requirements. Seeking to restore discipline, Kennedy established the Executive Stockpile Committee, while the Office of Emergency Planning created the Interdepartmental Disposal Committee to identify materials suitable for sale. Congress soon launched its own investigation, holding extensive hearings between 1962 and 1963 that declassified previously secret stockpile data. The hearings generated sharp criticism, including allegations that the Eisenhower administration had allowed stockpile holdings to grow far beyond strategic needs and that suppliers had earned excessive profits during periods of scarcity. Although the investigation produced no immediate legislative changes, the resulting transparency triggered unprecedented scrutiny. By the end of 1965, stockpile disposal sales had reached $1.6 billion.

Congress ultimately moved to reform the system. The Materials Reserve and Stockpile Act of 1965 replaced the Strategic and Critical Materials Stockpiling Act of 1946 and consolidated multiple federal inventories—including those acquired under the Commodity Credit Corporation and the Defense Production Act—into a single stockpile. At the time of consolidation, the government held 89 different materials valued at approximately $6 billion.

Even as policymakers focused on reducing domestic overstocking, global developments underscored the enduring strategic importance of secure mineral supply chains. In October 1960, Fidel Castro’s government nationalized the Cuban Nickel Company and the Nickel Processing Corporation, firms whose assets the U.S. government had invested more than $100 million in through the General Services Administration (GSA). Overnight, the United States lost control of a major foreign mineral asset. That same year, the Congo Crisis erupted following the Republic of Congo-Leopoldville’s independence from Belgium. Rich in uranium, the country became a flashpoint in the global Cold War. When Prime Minister Patrice Lumumba sought Soviet military assistance and rebuffed Western support, U.S. and Belgian operatives supported Colonel Joseph-Désiré Mobutu’s seizure of power and eventual execution of Lumumba. Washington subsequently backed Mobutu’s long rule, driven in part by concerns that Soviet influence could extend to the Congo’s uranium resources.

Globally, supply shocks continued throughout the decade. From 1966 to 1971, the United States complied with UN sanctions against Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe), banning imports of Rhodesian chrome to pressure its white minority regime. Congress enforced the embargo through legislation, including H.R. 1746. Although the ban eliminated a major supplier, its impact was softened by large releases of chromium ore from the National Defense Stockpile, which had already designated roughly 1.9 million tons as excess. In 1969, major labor strikes shut down production at the world’s two largest nickel producers, including the International Nickel Company’s operations in Ontario. In December 1969, President Richard Nixon formally determined that a release of up to 20 million pounds of nickel from the National Defense Stockpile was required for defense purposes.

By the end of the 1960s, the Cold War experience revealed a central paradox of U.S. critical minerals policy. The stockpile functioned effectively as a shock absorber during crises, yet repeated drawdowns without replenishment gradually eroded its strategic value. Policymakers remained reluctant to reimpose the heavy-handed controls of earlier wars, favoring market interventions only at moments of acute disruption. The result was a system increasingly oriented toward short-term stabilization rather than long-term resilience—a pattern that would resurface in later decades as new geopolitical and supply chain shocks emerged.

The Cold War: 1970s

After the heavy stockpile drawdowns of the 1960s, the 1970s brought renewed awareness of U.S. material vulnerabilities—but relatively little decisive action. A series of late-1960s shocks, including the UN sanctions on Rhodesia and the widespread labor disruptions in Canada, had forced Washington to confront the erosion of its domestic minerals base. By 1970, the United States consumed roughly 35 percent of the world’s mineral output while contributing only marginally to global production.

Congress responded with the Mining and Minerals Policy Act of 1970, which sought to strengthen domestic capacity by encouraging private industry to explore, mine, process, and recycle minerals more efficiently. The act required the secretary of the interior to submit annual assessments of mineral production, resource utilization, and depletion trends and helped spur the creation of the National Commission on Materials Policy. Over two years, the commission issued 198 recommendations emphasizing conservation and environmental protection.

This policy shift coincided with a broader national reckoning over environmental degradation. Public awareness had been galvanized by Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring, persistent smog in Los Angeles, and the 1969 Cuyahoga River fire. Between 1969 and 1973, Congress enacted sweeping environmental legislation that established the modern framework for clean air, clean water, and public health protections. While transformative, these laws carried significant implications for mining. Stricter permitting requirements and the withdrawal of large tracts of public land from mineral development dramatically reshaped the sector. Between 1968 and 1974, the share of public lands closed to mining rose from 17 percent to 67 percent. As a result, the very legislation intended to bolster domestic minerals production unfolded in an environment that increasingly constrained it. Many U.S. mining operations became uneconomic, accelerating closures and the relocation of production overseas.

At the same time, the global balance of mineral power was shifting. The Soviet Union and China remained largely self-sufficient in nonfuel minerals, with the former emerging as a major producer of iron ore, manganese, chromite, and tungsten. Both countries actively pursued overseas resource influence, particularly in Africa, Asia, and Latin America, heightening U.S. concerns about strategic vulnerability. Against this backdrop, Congress passed the Byrd Amendment in 1971, which prohibited embargoes on strategic materials imported from noncommunist countries. Although the law never explicitly referenced it, it effectively allowed the United States to resume importing Rhodesian chrome despite the 1966 UN sanctions. Advances in processing technology eventually diminished U.S. dependence on Rhodesian chrome, enabling the amendment’s repeal in 1977.

The 1973 Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) oil embargo delivered a stark demonstration of the United States’ exposure to foreign resource shocks. Nationwide fuel shortages emerged, and oil prices more than quadrupled. At the same time, rapid economic expansion in the United States, Japan, and Western Europe strained global supplies of copper, bauxite, and other industrial minerals, driving sharp price increases. In the first quarter of 1973 alone, U.S. output of goods and services rose by a record $35 billion. These pressures were compounded by efforts among mineral-producing countries to emulate OPEC’s market power. The International Bauxite Association, formed in 1974, sought coordinated price increases but quickly fractured as producers in the Caribbean and Australia failed to agree on price increases. Jamaica proved most successful in raising bauxite taxes, a move U.S. aluminum producers initially tolerated due to limited alternative supply options. An aluminum sector recession between 1974 and 1976, however, reduced Jamaica’s share of global bauxite production from 18.3 to 11.8 percent and accelerated the expansion of bauxite output in Australia, Brazil, Guinea, and Indonesia—countries that had not imposed higher taxes.

U.S. stockpile policy evolved amid these disruptions. In 1973, the National Security Council under President Nixon reevaluated the National Defense Stockpile and established new objectives based on three assumptions: (1) stockpiled materials would serve defense purposes only, (2) planning would account for simultaneous conflicts in Europe and Asia, and (3) imports would remain available throughout any emergency. Congress simultaneously reduced the stockpile planning horizon from three years to one. These more restrictive assumptions, combined with global mineral shortages, prompted significant stockpile sales. Between 1973 and 1974, $2.05 billion worth of material was sold or disposed of, with the proceeds redirected to the federal budget.

However, under President Gerald Ford, the National Security Council commissioned a comprehensive review of the stockpile in 1976. President Ford’s resulting guidance reinstated a three-year planning horizon and emphasized that the stockpile should support major war requirements for the three-year duration, full-scale industrial mobilization, and civilian economic needs. It also called for management through an Annual Materials Plan governing acquisitions and disposals.

The Strategic and Critical Materials Stock Piling Revision Act of 1979 formalized these changes. The act transferred policy oversight of the stockpile from the GSA to the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), while leaving operational responsibilities—storage, maintenance, purchases, and sales—with the GSA. It also established the National Defense Stockpile Transaction Fund within the Treasury Department to manage proceeds from disposals, reaffirmed the three-year planning horizon, and authorized presidential advisory committees to guide acquisition, processing, transportation, storage, security, and disposal decisions.

The stockpile revisions, institutional reforms, and growing recognition of U.S. import dependence during the 1970s laid the groundwork for the modern critical minerals debates that followed. Policymakers increasingly confronted the challenge of securing essential materials in a world where economic growth, environmental constraints, and geopolitical competition were deeply intertwined. By 1980, the United States had entered a new phase of minerals policymaking—defined by global interdependence, environmental limits, and elevated strategic risk. The decade made clear that neither domestic resource abundance nor stockpiling alone could guarantee security. Effective critical minerals strategy would instead require disciplined planning, resilient and transparent markets, and sustained engagement across a rapidly evolving global resource landscape.

The Cold War: 1980s

The early 1980s exposed deep structural weaknesses in the U.S. minerals base. Domestic production stagnated or declined, and a global recession shuttered mines across the country. These trends revived congressional concern that the United States was entering a period of heightened strategic vulnerability, particularly as dependence on foreign sources of critical and strategic minerals continued to rise. Congress responded with the National Materials and Minerals Policy, Research and Development Act of 1980—the second comprehensive national minerals policy after the 1970 Mining and Minerals Policy Act. The legislation called for more urgent and coordinated federal efforts to strengthen materials research, development, and production, while improving data collection and long-term planning. That same year, Congress also enacted the Deep Seabed Hard Mineral Resources Act, reflecting growing interest in diversifying supply beyond traditional terrestrial sources by authorizing environmental assessment, exploration, and potential commercial recovery of hard minerals from the U.S. deep seabed.

Ronald Reagan’s 1980 presidential campaign amplified these concerns, emphasizing the dangers of growing reliance on foreign sources for strategic and critical materials. Upon taking office, Reagan moved quickly to reorganize the nation’s stockpile program through the Annual Materials Plan—an interagency process led by FEMA and involving senior officials from the Departments of Defense, Commerce, Interior, Energy, Agriculture, State, and Treasury, as well as the CIA, GSA, and Office of Management and Budget. The process established annual acquisition and disposal targets for critical materials and sought to impose greater discipline and coherence on federal minerals planning.

The strategic rationale for reform was compelling. By 1983, the United States was almost entirely dependent on imports for chromium, cobalt, manganese, bauxite, and platinum-group metals. Rising domestic consumption and declining competitiveness deepened this reliance. Excluding iron and steel, the United States recorded a $2 billion mineral trade deficit in 1982. Earlier disruptions—including OPEC’s oil embargoes and political unrest in Zaire that temporarily interrupted cobalt flows—had already demonstrated the costs of dependence on unstable foreign suppliers. At the same time, policymakers acknowledged that imports provided essential benefits: Many minerals were unavailable domestically or prohibitively expensive to extract, and their unique physical properties were critical to emerging technologies in microelectronics, telecommunications, and advanced manufacturing. The challenge was not eliminating imports but managing their strategic risks.

In response, Reagan launched the first purchase program for the National Defense Stockpile in over 20 years in 1981, noting that, “It is now widely recognized that our nation is vulnerable to sudden shortages in basic raw materials that are necessary to our defense production base.” The administration also employed creative procurement mechanisms. In 1982, the United States negotiated a barter agreement with Jamaica, acquiring approximately 1.6 million tons of bauxite in exchange for U.S. dairy products, such as nonfat dry milk and milk fat. The arrangement strengthened the stockpile while allowing Jamaica to receive commodities rather than cash, continuing a long-standing U.S. practice of using barter authority to secure critical minerals for national defense.

The Reagan administration advanced additional proposals aimed at reducing U.S. vulnerability. Reagan called for expanded surveying of federal lands, observing that less than 0.3 percent of the country had ever been disturbed by mining, along with improved data sharing and tax incentives to support long-term, high-risk research. The GSA began a presidentially directed program to upgrade chromite and manganese ores into high-carbon ferroalloys, using proceeds from stockpile disposals to sustain domestic processing capabilities critical to defense production. Between 1984 and 1994, this effort was responsible for the conversion of nearly 1.4 million tons of chromite ore and 1 million tons of manganese ore. Reagan’s 1982 plan was seen as a step in the right direction, but it lacked the specificity needed to drive meaningful action. At a fundamental level, critics argued it failed to define what constitutes a critical mineral, assess how disruptions in individual mineral markets would affect the U.S. economy, and clarify the appropriate federal role in addressing these vulnerabilities.

By the mid-1980s, fiscal pressures again reshaped policy. Like Presidents Kennedy, Johnson, and Carter before him, Reagan turned toward liquidating portions of the stockpile to generate revenue. According to files declassified by the CIA, in 1985, he proposed selling select commodities to raise more than $3 billion for the U.S. Treasury, reducing stockpile acquisition goals from $16.3 billion to $5.4 billion. The proposal introduced a two-tier reserve system: a $600 million core stock of materials unavailable from domestic or reliable foreign suppliers and a $4.8 billion supplemental reserve intended to provide emergency flexibility.

Geopolitical developments further complicated minerals policy. Growing concern over U.S. dependence on South African mineral imports intersected with the anti-apartheid movement. Under the Comprehensive Anti-Apartheid Act of 1986, imports from South African parastatals were banned, except for strategic minerals deemed essential and unobtainable from secure alternatives. By the mid-1980s, the United States relied on imports for 54–100 percent of its needs for platinum-group metals, manganese, chromium, and cobalt. In 1988, the United States extended restrictions to strategic and critical minerals produced in South Africa altogether.

Stockpile governance shifted again in February 1988, when Reagan issued Executive Order 12626, designating the secretary of defense as National Defense Stockpile manager. The order centralized stockpile authority within the DOD, ending the operational roles of FEMA, GSA, and the Department of the Interior. The move reflected the administration’s view that minerals security was inseparable from national defense and required streamlined oversight.

By the late 1980s, a new set of geopolitical and technological forces was once again reshaping the global minerals landscape. The Cold War was drawing to a close, reducing the immediate risk of large-scale conflict, while advances in communications and consumer electronics elevated the strategic importance of REEs such as neodymium. At the same time, intelligence assessments pointed to declining Soviet exports of critical minerals to Western markets, and U.S. sanctions policy highlighted persistent vulnerabilities in South African supply chains. Taken together, these developments marked a turning point. As the United States entered the final decade of the twentieth century, policymakers carried forward a more acute awareness of the intertwined geopolitical, technological, and economic forces that would shape the next generation of critical minerals policy.

1990s

With the end of the Cold War, the long-running contraction of U.S. materials planning—underway since the 1960s—reached its apex. Defense planners increasingly assumed that future conflicts would be shorter, more mobile, and supported by reliable foreign suppliers. This shift led to a sharp reduction in stockpile requirements, signaling a departure from the massive wartime reserves of the past. The National Defense Authorization Act of 1993 specifically established new disposal targets for the National Defense Stockpile, effectively reducing requirements for most minerals to zero. By 1997, more than 99 percent of the National Defense Stockpile was deemed surplus to DOD requirements, and the department established a target of disposing of $2.2 billion in excess materials by 2000. As a result, the national stockpile, once the backbone of wartime industrial power, had become a marginal institution focused largely on disposal rather than preparedness.

At the same time, the globalization of mineral supply chains and China’s emergence as a dominant producer fundamentally altered the strategic landscape. Nowhere was this more evident than in rare earth production. Regulatory misclassification of REEs under thorium controls imposed legal and operational constraints on the United States’ primary mine at Mountain Pass. Meanwhile, beginning in the late 1980s, China aggressively subsidized REE mining and processing. By the 1990s, China’s low-cost production made it economically attractive for U.S. firms to outsource refining while avoiding domestic environmental and regulatory burdens. Over time, this shift eroded the technical expertise and industrial capacity required to sustain a domestic REE supply chain. By 1998, the United States had sold its reserves of the only stockpiled REE, yttrium. The DOD had never even classified REEs as strategic materials, further cementing the country’s dependence on foreign production and signaling a new era in U.S. materials vulnerability.

Domestic institutional support for mining and minerals research eroded in parallel. In 1995, a congressional conference committee recommended abolishing the Bureau of Mines, and in 1996 the bureau—once responsible for domestic mine oversight and wartime exploration missions—was officially closed, with some functions transferred to other agencies. Together, these developments marked a profound inflection point. As the United States entered the post–Cold War era, confidence in globalization, allied supply, and just-in-time logistics displaced earlier models of redundancy and resilience. The dismantling of stockpiles, erosion of domestic capacity, and consolidation of supply chains abroad would shape—and ultimately constrain—U.S. critical minerals policy for decades to come.

Enduring Lessons from Twentieth-Century Minerals Policy

- Mineral security is an industrial policy problem, not a stockpile problem.

Throughout the historical record, stockpiles proved valuable as short-term shock absorbers, but they never functioned as a substitute for durable industrial capacity. Stockpiles could cushion temporary disruptions, stabilize markets, or buy time during crises, yet they could not replace resilient supply chains, domestic and allied processing capacity, skilled workforces, or transparent and well-functioning markets. Where these broader systems were weak or absent, stockpiles merely delayed the consequences of structural dependence.

Repeatedly, U.S. policymakers treated stockpiling as a discrete technical solution rather than as one component of a broader industrial strategy. This narrow framing masked deeper vulnerabilities: erosion of refining and conversion capacity, offshoring of technical expertise, underinvestment in exploration and processing, and fragmented coordination between government and industry. When stockpiles were drawn down without parallel investments in supply chain resilience, the United States emerged more exposed than before. The historical lesson is clear: Mineral security requires sustained industrial policy—aligning incentives, infrastructure, workforce development, and market governance—not episodic reliance on inventories that cannot, on their own, sustain long-term competitiveness or strategic autonomy. - Industrial capabilities decay faster than they are rebuilt.

During the post–Cold War period, confidence in globalization and market efficiency obscured the gradual erosion of U.S. minerals capabilities. As domestic expertise, workforce pipelines, and processing know-how began to decline, the loss occurred quietly and was rarely recognized as a strategic risk. Once this erosion set in, it proved rapid and largely irreversible in the short term.

The REEs experience of the 1990s illustrates this dynamic clearly. Although the United States continued to mine rare earth ore at Mountain Pass, regulatory misclassification, rising environmental compliance costs, and the availability of heavily subsidized Chinese processing made it economically rational for firms to offshore separation, refining, and downstream manufacturing. Over time, this shift eliminated domestic processing expertise and hollowed out the specialized workforce required to sustain the supply chain. When strategic concerns later reemerged, restoring capability proved far more complex than reopening a mine. It required rebuilding entire industrial ecosystems—processing infrastructure, skilled labor, regulatory competence, and downstream demand—an effort measured in decades, not years. The broader lesson is that market reliance can dismantle industrial capacity long before vulnerabilities become visible, and once lost, those capabilities cannot be rapidly regenerated through emergency policy alone. - Processing capacity matters as much as extraction.

Repeatedly, the United States possessed (or could readily access) raw mineral resources, but lacked the processing and conversion capacity needed to translate those inputs into usable industrial and military materials. During World War I, shortages emerged not because copper, zinc, or manganese were absent, but because smelting, alloying, and coordinated production lagged demand, forcing late-stage federal intervention through the War Industries Board. Similar dynamics reappeared during the Korean War, when the federal government was compelled to invest directly in processing infrastructure, such as copper and manganese facilities, because private capacity was insufficient to meet wartime requirements. These episodes underscored a recurring reality: Extraction can be accelerated under crisis conditions, but processing capacity requires technical expertise and sustained policy support. - Mineral security is never permanent—only managed.

Throughout the twentieth century, U.S. critical minerals policy followed a recurring cycle of crisis, mobilization, and downsizing. Wartime scarcity triggered extraordinary government intervention—stockpiling, subsidies, public procurement, and foreign supply acquisition—while peacetime stability bred complacency and rapid drawdowns. This pattern of strategic whiplash prevented the emergence of a durable, long-term industrial strategy, as firms struggled to sustain investment amid constantly shifting federal priorities. The consequences of retrenchment surfaced later. As the United States dismantled strategic programs and liquidated Cold War stockpiles, China pursued the opposite course. It expanded state-backed mining, subsidized domestic refining, and leveraged price competition to capture global market share. What U.S. policymakers viewed as fiscal prudence in the 1990s became a strategic liability by the 2020s, leaving the United States exposed to supply shocks, geopolitical coercion, and an industrial base unable to scale rapidly for national security needs.

The post–Cold War “peace dividend” accelerated this dynamic. Policymakers assumed that globalized markets would ensure reliable access to minerals, and that geopolitical competition over raw materials had become an artifact of the past. Experience has proven otherwise. Mineral security cannot be episodic. It must be treated as a permanent pillar of national power, requiring continuous stewardship rather than crisis-driven improvisation. - Overconfidence is the most persistent vulnerability.

Across a century of U.S. minerals policy, the most damaging failures emerged not in moments of crisis, but during periods of confidence. When globalization appeared irreversible, markets efficient, and geopolitical stability durable, policymakers consistently dismantled planning frameworks, liquidated stockpiles, and allowed domestic capabilities to erode. Strategic success bred strategic neglect. The assumption that markets would self-correct, allies would remain reliable, and disruptions would be short-lived proved repeatedly fragile. This pattern was most evident after major inflection points: following World War I, after the perceived stabilization of Cold War supply chains in the 1960s, and most starkly in the post–Cold War 1990s. In each case, confidence in economic integration and technological progress displaced earlier emphasis on redundancy and preparedness. The result was not immediate failure, but latent vulnerability that only became visible once conditions shifted. The takeaway is not that globalization or markets are liabilities, but that complacency is. Mineral security deteriorates fastest when it is assumed to be assured, underscoring the need for institutionalized vigilance even in periods of apparent stability. - Stockpiles are only as effective as the assumptions behind them.

Across multiple eras, U.S. stockpile policy failed not because stockpiles were inherently ineffective, but because the planning assumptions embedded within them proved fragile. Repeatedly, policymakers assumed short wars, uninterrupted access to foreign suppliers, stable alliances, and smoothly functioning markets. These assumptions shaped stockpile size, composition, and drawdown decisions—often in ways that left the nation exposed when conditions changed. When geopolitical shocks, market disruptions, or technological shifts outpaced planning models, stockpiles either proved insufficient at the moment of need or had already been liquidated during periods of perceived stability. The historical record shows that stockpiles function best as insurance against uncertainty, not as static inventories optimized for best-case scenarios. Their effectiveness depends less on volume than on realistic threat assessments, adaptive planning horizons, and sustained political commitment to preparedness even when risks appear remote. - Minerals diplomacy works best when embedded in broader statecraft.

History shows that the most durable arrangements for securing access to critical minerals emerged not from narrow commodity deals, but from minerals being embedded within broader frameworks of diplomacy, trade, development, and security cooperation. When minerals policy was treated as part of a wider statecraft tool kit—integrated with aid, infrastructure finance, technical assistance, and alliance management—the United States was better able to secure reliable access while managing political risk.

Cold War–era development diplomacy offers clear examples. Under the Point Four program, U.S. technical assistance missions helped identify mineral deposits, modernize transportation networks, and establish regulatory frameworks across Latin America, Africa, and Asia. These efforts expanded supply while aligning mineral access with host-country development goals, reducing perceptions of exploitation. Similarly, barter arrangements during the 1950s and 1980s—such as exchanges of U.S. agricultural commodities for Jamaican bauxite or Indian manganese—enabled the United States to secure strategic materials while providing tangible economic benefits to partners. By contrast, approaches that relied primarily on coercion or unilateral control proved brittle. Sanctions regimes, export controls, and preclusive purchasing could temporarily deny adversaries access, but they frequently generated political backlash, encouraged supplier diversification away from the United States, or accelerated resource nationalism. Even when successful in the short term, these tools rarely produced lasting access without complementary diplomatic and economic engagement.

The historical lesson is that minerals diplomacy is most effective when aligned with partner interests and embedded in broader statecraft. Infrastructure financing, workforce development, security cooperation, and trade integration created relationships resilient to political change and market volatility. When minerals were treated instead as isolated commodities, detached from development or alliance considerations, access proved contingent and fragile. - Domestic production and environmental policy must be reconciled.

The 1970s demonstrated that promoting domestic mineral production while simultaneously tightening permitting requirements and withdrawing large areas of land from development created structural contradictions that undermined both objectives. Policymakers articulated the need to strengthen U.S. mineral supply chains through legislation such as the Mining and Minerals Policy Act of 1970, yet this ambition coincided with a rapid expansion of environmental regulation and land-use restrictions. New permitting regimes lengthened project timelines, raised compliance costs, and increased uncertainty for investors, while the withdrawal of substantial portions of federal land sharply constrained access to prospective mineral resources.

When environmental and industrial objectives were pursued in isolation, the outcome was not cleaner domestic production, but offshoring. Mining and processing activity migrated to jurisdictions with weaker environmental standards, less stringent permitting, and lower costs, exporting both emissions and supply chain risk rather than reducing them. This shift hollowed out U.S. capacity while increasing dependence on foreign sources and limiting the government’s ability to influence environmental performance abroad. Environmental protection and domestic production are not necessarily incompatible, but they must be designed together to be effective. Durable mineral security requires integrating environmental safeguards into industrial policy from the outset. It requires aligning permitting, land management, technology development, and market incentives, so that domestic mineral production remains both environmentally responsible and economically viable. - Allies are indispensable, but not frictionless.

Throughout the twentieth century, allied and partner countries were indispensable to U.S. access to critical minerals. From colonial-era supply chains to Cold War barter diplomacy, alliance-based sourcing enabled the United States to compensate for domestic shortfalls and reduce exposure to adversarial suppliers. Yet history shows that allied access was never frictionless or guaranteed. Political change, labor unrest, nationalism, sanctions, and domestic instability repeatedly disrupted supplies even from countries considered reliable partners. Examples recur across eras. During World War I, reliance on Russian platinum collapsed after the Bolshevik Revolution. In the 1960s and 1970s, labor strikes in Canada disrupted nickel supplies, while sanctions on Rhodesia forced the United States to navigate tensions between geopolitical commitments and material needs. During the Cold War, decolonization transformed resource-rich territories into sovereign states that asserted greater control over mineral assets, altering pricing, taxation, and access terms. Even close partners periodically leveraged minerals for domestic political or economic objectives, complicating supply assumptions.

These episodes underscore a consistent theme: Alliances reduce risk but do not eliminate it. Political alignment does not immunize supply chains from domestic pressures within partner countries, nor from broader geopolitical shifts. Effective minerals strategy therefore requires diversification across allies, contingency planning for allied disruptions, and continuous diplomatic engagement to manage reliability. Treating allied access as assured has proven repeatedly costly; treating it as conditional and actively managed has proven far more resilient.

Conclusion

History makes clear that U.S. critical minerals vulnerability is not the product of a single policy failure, but of a recurring pattern: crisis-driven mobilization followed by prolonged retrenchment. Across wars, technological revolutions, and geopolitical shifts, the United States repeatedly demonstrated that mineral security is not guaranteed by geology, markets, or alliances alone, but by sustained institutional capacity, industrial coordination, and strategic foresight. When these systems were actively managed, the United States proved capable of rapidly mobilizing materials at scale; when they were dismantled in periods of perceived stability, vulnerabilities accumulated quietly and surfaced only when conditions changed. The post–Cold War drawdown marked the most extreme expression of this cycle, leaving the country exposed to supply shocks, coercion, and industrial fragility at precisely the moment minerals once again became central to national power. The central lesson of a century of experience is therefore straightforward but demanding: Critical minerals security must be treated as a permanent pillar of national strategy, requiring continuous stewardship rather than episodic intervention. Rebuilding resilience today will require not only new investments and policies, but the deliberate reconstruction of capabilities, institutions, and habits that history shows are far easier to lose than to restore.

Gracelin Baskaran is director of the Critical Minerals Security Program at the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) in Washington, D.C. Samantha Dady is a research associate with the CSIS Critical Minerals Security Program.

This report is made possible by general support to CSIS. No direct sponsorship contributed to this report.