Starting Up the Competition: Japan’s Mobile Software Act

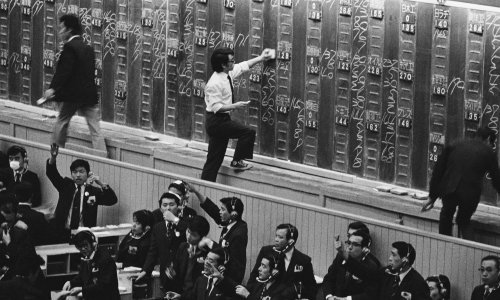

Photo: Bettmann/Getty Images

Introduction

Japan’s Mobile Software Competition Act (MSCA) took effect on December 18, 2025, joining a global wave of ex-ante digital market regulation. By designating Apple, Google, and iTunes K.K. as regulated providers, the MSCA opens mobile software distribution beyond the App Store and Google Play, permits alternative payment systems with lower commission fees, and expands consumer access to alternative browsers and search engines.

The MSCA is already reshaping market behavior. Greater distribution and payment flexibility allows developers to bypass the 15-30 percent commission fees on in-app purchases, potentially transforming enterprise profit margins. According to Kyodo News, 70 percent of surveyed Japanese smartphone games are already using external payment systems.

As Japan enters this next phase of competition policy, however, success will depend not on constraining Apple and Google, but on producing durable domestic companies. Whether digital payment startups can attract customers, game developers can sustain higher-margin business models, or experimental apps and alternative app stores can scale will require complementary developments in venture capital, exit pathways, and labor markets.

A Look at the Mobile Software Competition Act

The MSCA operates as complementary legislation to Japan’s Antimonopoly Act (AMA). Enacted in 1947, the AMA established broad, cross-sectoral prohibitions against anticompetitive practices like abuses of bargaining positions, mergers and acquisitions that restrain competition, and exclusive dealing. The AMA also created the Japan Fair Trade Commission, which enforces the AMA by conducting investigations and market surveys, issuing cease-and-desist orders and levying fines to non-compliant firms, and proactively implementing other competition policies like the MSCA.

While the AMA remains the foundation of Japan’s competition regime, the Japan Fair Trade Commission has argued that the Act is ill-suited for smartphone software. As a result, the MSCA was designed as a specialized, forward-looking framework. In areas related to smartphone operating systems, application stores, browsers, and search engines, the MSCA supersedes the AMA and represents Japan’s first major ex-ante competition policy. As the Japan Fair Trade Commission has explained, in these markets it is difficult to “restore fair and free competition … [because] self-correction by market mechanisms such as new entries is difficult and it takes a remarkably long time to demonstrate anticompetitive activities in response to individual cases under the Antimonopoly Act.”

Under the MSCA, a company becomes a designated provider if its operating system, application store, browser, or search engine has more than forty million monthly users in Japan during the fiscal year. Designated providers are prohibited from engaging in anti-steering conduct, using data obtained through their platforms to compete with third parties, and self-preferencing their own services.

Landscape of SME Growth in Japan

The real test of the MSCA, however, lies in whether Japanese enterprises can leverage the market openings to enhance competition.

As the world’s fourth-largest economy, Japan’s venture capital ecosystem remains underdeveloped. While venture capital investment levels are not significantly lower than those of other G7 economies, the scale of investment falls short of government targets. Total venture investment increased from 34.9 billion yen in 2011 to 329.3 billion yen in 2021, yet Japan remains far from its 2022 five-year target of reaching 10 trillion yen (approximately $67.6 billion) in annual startup investment by 2027. In 2024, annual startup investment totaled 779.3 billion yen, with more than 93 percent of investments below 1 billion yen.

Exit pathways play a central role in directing the ambition and growth trajectories of startups. Historically, the Tokyo Stock Exchange has been criticized for listing practices that encouraged early-stage IPOs. Over the past decade, offerings valued below 10 billion yen accounted for approximately 82 percent of all IPOs, a greater share than counterparts like Hong Kong. In response, the Exchange amended its listing standards to require firms to maintain a market capitalization of at least 10 billion yen after five years, up from the previous 4-billion-yen threshold. Even so, the number of startup IPOs decreased prior to these reforms, down from 66 in 2021 to 47 in 2024. During the same period, merger-and-acquisition activity and asset transactions increased, suggesting a gradual shift in exit pathways.

These shifts in exit pathways adjust the incentives of founders and financiers alike. When early IPOs are commonplace, founders steer towards quick liquidity instead of scaling with multiple seed rounds of private investment that can support longer development cycles. Higher thresholds for IPOs, combined with increasingly viable M&A and asset transactions, could empower firms to pursue more ambitious technological ventures.

For Japanese startups, established corporates are both rivals for talent and market share and key partners in venture investment. The practice of lifetime employment has historically benefited large firms and made entrepreneurship risky for early- and mid-career professionals. This dynamic has begun to change. Over the past decade, midcareer hiring has risen by nearly 20 percentage points – potentially creating a window for start-up founders to alternate between corporate and startup employers.

Concurrently, the distinction between conglomerates and startups has blurred. Corporate venture capital arms now contribute to more than half of all venture capital deals in Japan. These changes suggest a gradual reorientation of Japan’s exits away from early public listings and towards an environment that enables competition and supports firm scaling.

International Lessons in the Road Ahead

For American and European policymakers alike, Japan’s approach to digital regulation is notable as a middle path. Unlike the United States' case-by-case antitrust enforcement and the European Union’s Digital Markets Act, Japan has balanced broad ex-post regulation with targeted ex-ante enforcement to prevent harmful conduct before it occurs (for a more critical view, read Sangyun Lee’s article). While it is too early to assess outcomes, this hybrid model may offer a compelling template for countries seeking to promote investment and innovation while preserving open platforms and consumer choice.

The MSCA arrives at a pivotal moment for Japan’s digital economy. Crucially, the MSCA will indicate whether regulatory intervention can function as industrial policy – catalyzing economic renewal and cultivating globally competitive firms.

Japan's economic trajectory carries implications that extend far beyond its borders. From a postwar economic miracle to contested lost decades, Japan’s economy has undergone explosive growth and perpetual stagnation in equal measure. In current dollars, Japan's economy grew 66-fold from 1960 to 1988. In 2024, Japan's GDP was lower than it was more than 30 years prior, with only 10 percent wage growth in nominal terms from 1991 to 2020.

A strong, innovative Japan is essential for American economic security. Japan is the largest foreign investor in the United States ($819.2 billion) and holds more American sovereign bonds than any other country ($1.2 trillion). In 2024, U.S.-Japan trade in goods and services totaled $319.2 billion. Moreover, as a deep technological partner, Japan is a global leader in strategic fields including industrial robotics, the complementary metal oxide semiconductor (CMOS) image sensor market, and wafer crystal machining.

By lowering transaction costs for developers and restricting anti-steering practices, the Act creates real opportunities for alternative app stores, payment systems, and operating systems to gain traction. Whether these regulatory openings translate into durable competitive advantages, however, will depend on how effectively firms can scale within Japan’s broader innovation ecosystem.

Ultimately, the MSCA is an intervention operating alongside efforts across workforce norms, venture finance, and stock exchange reform. The promise of competition policy can only be realized through these interlocking reforms – otherwise, Japan’s framework will penalize incumbents without empowering emergent challengers.

Richard Gray is a program coordinator and research assistant with the Economics Program and Scholl Chair in International Business at the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) in Washington, D.C.

For more analysis on how states interact in a transitioning global economy, check out our blog series, Charting Geoeconomics.