Taking on Cyber Scams: Ideas for Congress

Photo: nevodka.com/Adobe Stock

Nearly three-quarters of Americans have experienced an online scam, fueled by advances in technologies like AI that enable scammers to defraud victims more quickly and effectively. In 2024, these scams caused $16.6 billion in losses in the United States. Globally, losses exceed $63.9 billion.

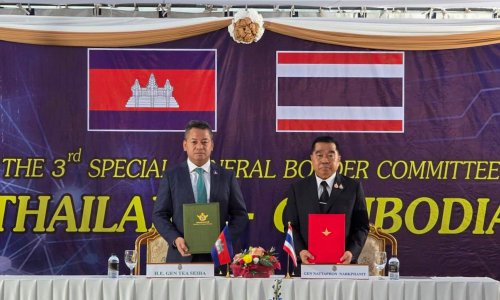

These lucrative scams are orchestrated by sophisticated criminal networks, primarily in Southeast Asia, that traffic victims to scam centers and force them to defraud people. These transnational criminal organizations control sprawling networks of illicit service providers around the world, and the funds from the scams have funded drug, arms, and sex trafficking. It is estimated that more than 250,000 victims from at least 100 countries are currently trapped in scam centers in Southeast Asia.

The threat to Americans is grave, yet a bipartisan majority of U.S. adults believe the federal government is doing a poor job tackling it. To chart a new path, Congress must deliver real protections for U.S. citizens. This analysis reviews five proposed bills to protect Americans and disrupt scam networks:

- 2544, H.R.2978—GUARD Act

- 2670, H.R.3523—STOP Scammers Act

- 2019, H.R.4936—TRAPS Act

- R.5490—Dismantle Foreign Scam Syndicates Act

- 2950—SCAM Act

S.2544, H.R.2978—GUARD Act

The Guarding Unprotected Aging Retirees from Deception (GUARD) Act would allow state, local, and tribal law enforcement agencies to use eligible grant funds received under several Department of Justice (DOJ) programs and under Section 1401 of the Violence Against Women Act Reauthorization Act of 2022 to investigate elder fraud, “pig butchering” scams, and other financial crimes. The funds may be used to

- hire and train personnel;

- buy software and tools;

- improve data collection and reporting;

- run tabletop exercises to improve coordination between law enforcement agencies and banks; and

- appoint a financial sector liaison.

The bill also requires the secretary of the treasury and the director of the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network, in consultation with other federal partners, to submit a report to Congress within two years that estimates scam prevalence and foreign involvement in scams, financial losses, enforcement actions, and the amount of funding allocated to address the problem. Finally, the GUARD Act explicitly authorizes federal law enforcement agencies to help state, local, and tribal authorities with advanced tools like blockchain to track and investigate scams.

Analysis

Limiting agencies to existing federal grants without providing additional, dedicated funding may hinder their ability to meaningfully scale up their capabilities. Most funds from these programs come from FY 2024 and may already be allocated or committed, and funding for programs that still exist are not keeping pace with the increasing threat. For example, the DOJ’s Economic, High-Technology, White Collar, and Internet Crime Prevention National Training and Technical Assistance Program received $12 million in funding in FY 2024 and did not receive any funding in FY 2025. The DOJ requested $4.8 million for FY 2026, a 40 percent drop from the amount received in FY 2024.

Moreover, requiring only a single report may not be the most effective approach. Given how rapidly scams evolve, a one-time report risks becoming outdated much too rapidly for it to provide much value. Congress may consider requiring quarterly briefings to go along with annual updates to provide more timely information.

S.2670, H.R.3523—STOP Scammers Act

The Strengthening Targeting of Organized Predatory (STOP) Scammers Act directs the secretary of the treasury, in coordination with the attorney general, to designate groups that attempt to scam U.S. citizens or permanent residents into giving money or other assets as Foreign Financial Threat Organizations (FFTOs), a new designation category. Once designated, the Treasury Department may freeze or otherwise restrict their U.S. assets, with penalties similar to those imposed on terrorist groups. The legislation also includes measures to prevent FFTOs from contacting U.S. permanent residents via phone, internet, or email and measures to limit their access to internet and cellular services.

The bill also requires the secretary of the treasury to submit a report within two years, and then annually thereafter, listing the designated organizations, how they were identified, the amount of money seized, and the amount returned to scam victims.

Analysis

The bill’s provisions aimed at making it more difficult for scammers to contact potential U.S. victims could limit their reach, making scams targeting Americans less lucrative. However, these criminal networks are resilient and tech-savvy, so Congress, law enforcement, and other stakeholders should remain vigilant to anticipate and adapt to evolving tactics.

Furthermore, while FFTO designation and asset freezes may have a limited direct impact on foreign criminal groups, they serve as an important signaling mechanism that demonstrates U.S. resolve to disrupt transnational scam operations. These measures also send a clear message to international partners, industry, and financial service providers that complicity with such groups will have consequences.

Finally, implementation must require robust evidentiary standards and other protections as a requirement for FFTO designation to prevent unintended harm to legitimate entities. Criminal groups frequently operate under the guise of legitimate businesses, using front companies to evade regulations, commit fraud, and launder illicit funds, complicating designation and running the risk that a legitimate company could be wrongly targeted.

S.2019, H.R. 4936—TRAPS Act

The Task Force for Recognizing and Averting Payment Scams (TRAPS) Act would create a task force to study current trends in payment scams, identify effective prevention methods, and recommend improvements to enhance response efforts.

The task force would be chaired by the secretary of the treasury and have representatives from federal agencies involved in consumer protection, financial regulation, law enforcement, and communication, as well as representatives from the financial sector, technology companies, and victim or scam support groups. It would be required to submit a report within one year detailing the findings and recommendations and provide annual updates for three years.

Analysis

Currently, there is no unified federal strategy or coordination mechanism for combating scams, so the task force proposed in the TRAPS Act may be a first step toward bringing some relevant stakeholders together. Its composition positions the task force to focus specifically on the financial and regulatory aspects of scams. However, it is not structured to address the international aspects of the problem, so it may serve as an important complement to the task force proposed in H.R.5490—Dismantle Foreign Scam Syndicates Act or S.2950—SCAM Act, but Congress should be careful not to duplicate its efforts.

One major obstacle to the success of this task force may be the lack of dedicated funding. Other task forces without funding have faced challenges in maintaining the long-term effectiveness and sustainability of their operations. For instance, the Forced Labor Enforcement Task Force (FLETF), an interagency group responsible for compiling a list of companies known to utilize forced labor, does not have its own funding but instead requires agencies to reallocate their own resources and personnel. While the FLETF added 144 entities to the list in its first three years, the task force has not added any companies since January 15, 2025. The lack of dedicated funding may be responsible for this stagnation, as the participating agencies divert personnel and resources from the FLETF to other priorities. The TRAPS Act may face similar difficulties if it does not have consistent funding support.

H.R.5490—Dismantle Foreign Scam Syndicates Act

The Dismantle Foreign Scam Syndicates Act would establish an interagency task force to develop and implement a strategy to shut down scam centers, dismantle criminal networks, and hold complicit actors and states accountable.

Chaired by the secretary of state, the task force would include leaders from the Departments of State, Justice, Homeland Security, and the Treasury, as well as the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission, the FTC, and the Federal Communications Commission. It would also consult with state and local law enforcement as well as nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) and private sector organizations. After developing the strategy, the task force would submit a report within 360 days of the creation of the strategy and annually thereafter for five years.

The bill further allows the president to impose sanctions on foreign persons who run or provide support for scam operations, as well as government officials who benefit from scam compounds. Finally, it allows the secretary of state to carry out programs to support victims of human trafficking. Several provisions were included in the Department of State Reauthorization Bill, which passed out of the House Foreign Affairs Committee in September 2025.

The contents of this report are detailed in the analysis of this bill, which is located at the end of the next section.

S.2950—SCAM Act

The Scam Compound Accountability and Mobilization (SCAM) Act similarly calls on the secretary of state, in consultation with the attorney general, the secretary of the treasury, and other relevant department and agency heads, to develop a strategy designed to counter scam centers. After developing the strategy, relevant agencies would establish a task force responsible for implementing the plan and monitoring the situation, which would submit annual reports to Congress and disband six years after its establishment. This bill also allows the president to impose sanctions on relevant actors and organizations.

Analysis

The passage of either bill could be a critical step toward a much-needed national strategy to combat scams. While there is significant overlap between the two bills, each has areas where it is stronger than the other:

- Funding: The initial version of H.R. 5490—Dismantle Foreign Scam Syndicates Act—would have appropriated $30 million in FY 2026 and FY 2027 for the Department of State to develop and implement the strategy. However, the December 2025 committee markup removed the dedicated funding. Instead, it directs the secretary of state to use funds otherwise authorized to be appropriated to carry out section 481 of the Foreign Assistance Act of 1961 to create the strategy. Section 481 establishes a broad authority for the United States to assist other countries in combating international narcotics trafficking, money laundering, and other transnational crime. This means that funding for this effort will have to compete with other priorities under section 481 and may be insufficient to support the task force and strategy development. S.2950 also does not allocate funding.

- Reporting: The reporting requirements laid out in H.R. 5490—Dismantle Foreign Scam Syndicates Act—are more comprehensive and detailed than those in S.2950—SCAM Act. While S.2950 requires only a “review of . . . the overall state of scam compounds” and a list of enabling and impacted countries, H.R.5490 mandates reporting on:

- sanctioned entities and individuals;

- estimates of funds stolen, intercepted, seized, or returned;

- estimates of how many victims of human trafficking are being held in scam centers;

- estimates of the total number of people complicit in scam center operations;

- a list of known scam centers and whether they are proliferating to new locations; and

- recommendations on the programs the Department of State should support to effectively implement the strategy and the level of funding needed.

- Task Force Composition: H.R. 5490—Dismantle Foreign Scam Syndicates Act—specifically directs the task force to consult with state and local law enforcement entities, NGOs, and relevant private sector actors in developing the strategy. In comparison, the task force required by S.2950—SCAM Act—is composed of relevant federal agency heads and does not mandate coordination with other entities. Nonfederal partners bring unique insights that a task force composed solely of federal agencies may not capture, so requiring consultation with these stakeholders is essential to creating a comprehensive and agile strategy.

- Support for Victims of Human Trafficking: H.R. 5490—Dismantle Foreign Scam Syndicates Act— authorizes the secretary of state to run programs that support victims who were trafficked to scam centers using funds appropriated to carry out section 481 of the Foreign Assistance Act of 1961. By contrast, S.2950—SCAM Act—requires the strategy to include the goals and performance measures for the government’s response to supporting trafficking survivors but does not specifically authorize victim support programs.

Next Steps

While the proposed bills offer a great start, they could be strengthened by taking the following steps:

Create a unified scam reporting platform and improve information sharing with key stakeholders. Currently, victims may report to different entities, such as the FBI’s Internet Crime Complaint Center, the FTC’s Report Fraud, and the state or local police, but this data is not compiled in a unified place. Instead, the U.S. government should establish a single, centralized repository where victims can report scams, making it less confusing for victims to know where to report an incident.

Similarly, the government and industry should work together to establish a single reporting platform where companies can easily share scam information amongst each other and with law enforcement and the government. This would make it easier to analyze trends and catch bad actors across platforms.

In a positive step, S.2019, H.R.4936—TRAPS Act—requires the task force to submit a report that offers recommendations on how to harmonize data collection among federal, state, and tribal authorities. Similarly, S.2544, H.R.2978—GUARD Act—allows state, local, and tribal law enforcement agencies to repurpose certain federal funds to encourage improved data collection and reporting.

- Invest in public awareness and evidence-based scam education to reduce the number of Americans who fall victim to scams. Currently, public awareness campaigns are fragmented across agencies. For example, the FBI has its “Take A Beat” campaign, the FTC has the “Pass it On” campaign, and the U.S. Social Security Administration hosts “Slam the Scam Day.” To better raise public awareness, Congress could consider designating one agency to lead this effort and appropriating funding for the creation of these materials. The scam reporting website could also house these educational materials, helping all citizens know where to find the information they need.

- Allocate consistent funding for scam prevention. There is currently no stable, multiyear funding for scam prevention and victim recovery. Successful implementation of these bills will require agencies to hire and train additional staff and invest in new technology and other resources, making additional funding essential.

- Consider how to support smaller and less well-resourced companies, including by providing grants or training programs. The United States has more than 4,000 banks, some of which are small and may lack the technical capacity, staffing, and financial resources needed to effectively identify and stop scam activity. For example, Kentland Federal in rural Indiana has only two employees. Similar challenges exist for other small online payment providers, social media platforms, and dating sites, which may lack the scam-prevention infrastructure of larger companies.

Scams pose a critical threat to Americans and others around the globe. Beyond the billions of dollars in losses, scams cause severe individual emotional trauma and erode trust in public institutions like banks, law enforcement, and digital platforms. Further, scam centers destabilize regional governments by fueling corruption and undermining the rule of law while strengthening the power of criminal networks, often linked to drug trafficking and other illicit activities. Luckily, Congress appears to be poised to pursue a more aggressive campaign to tackle this complex issue with these bills. Congress should demand results and seek accountability for progress in combating this threat.

Julia Dickson is an associate fellow for the Intelligence, National Security, and Technology Program at the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) in Washington, D.C. Emma Gargiulo is an intern with Congressional and Government Affairs at CSIS.